Coccidiosis is a disease caused tiny, single-celled parasitic organisms called protozoa. In recent years the condition has become more prevalent with the intensification of cattle and sheep farms in Ireland and the UK.

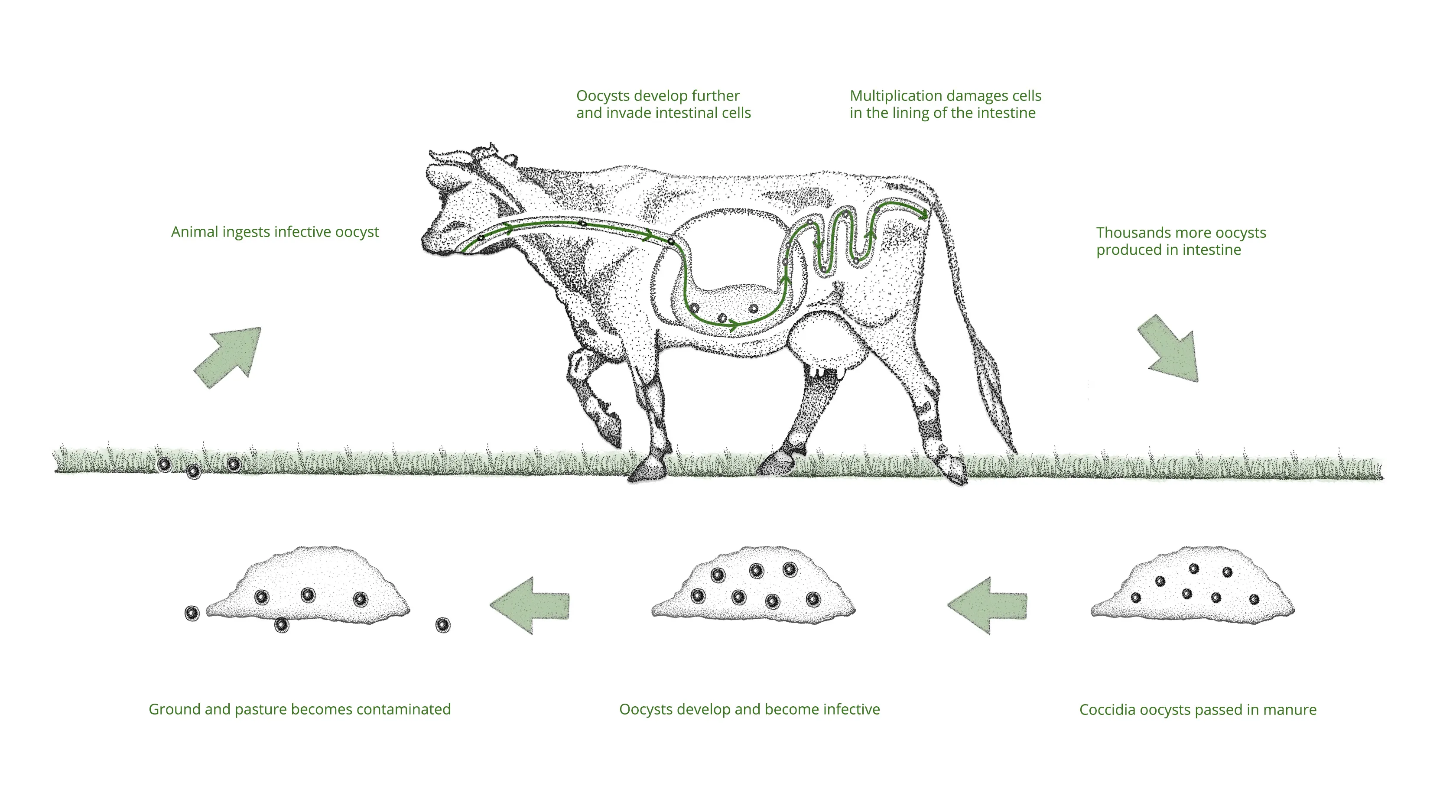

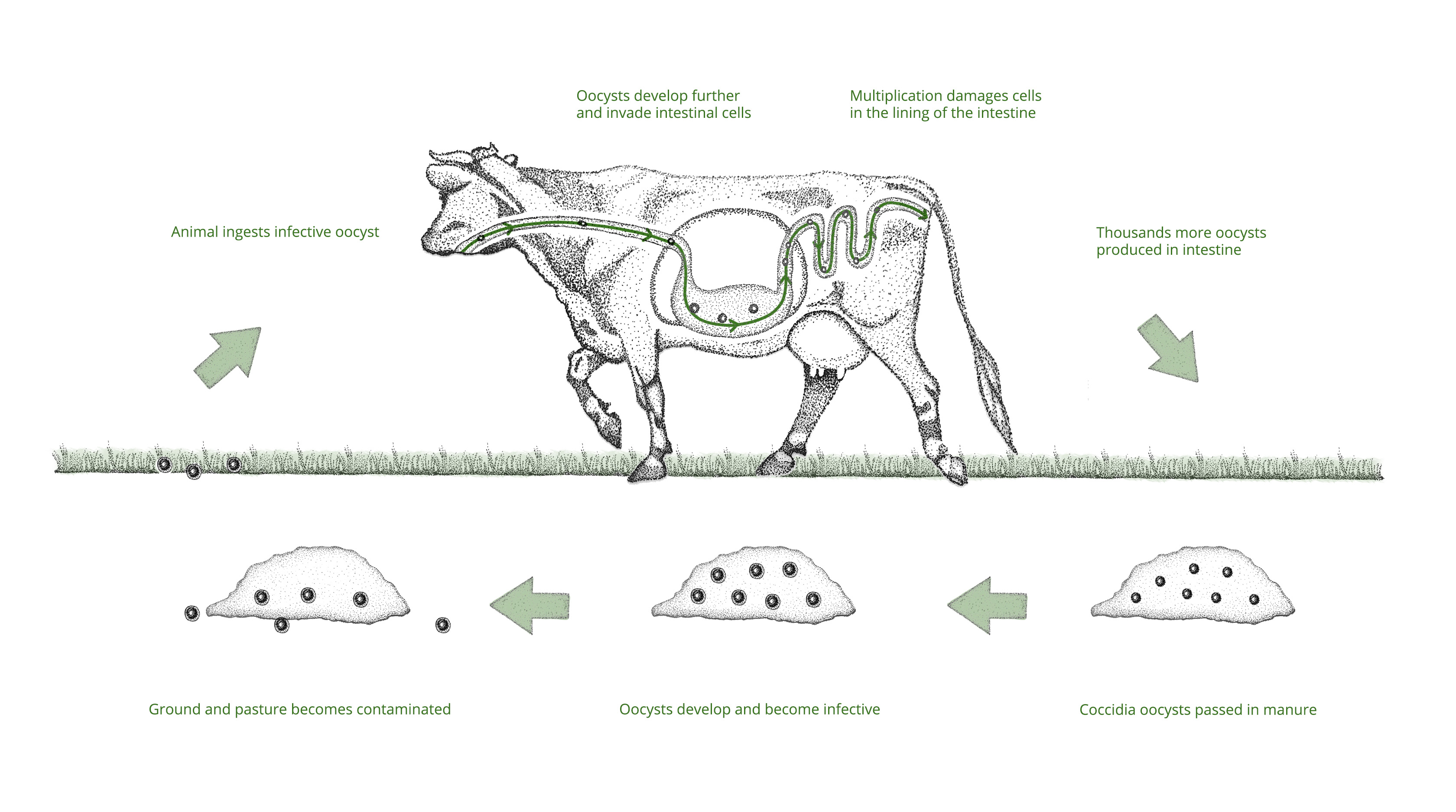

Coccidia oocycts are numerous in the farm animal’s environment and exposure of livestock to these at some point is inevitable. Oocysts are extremely resilient and can survive in most environments for over 12 months. Under the right conditions they become infective and can cause harm to our animals. Unfortunately, these conditions mirror the warm, moist climate found here in Ireland and the UK. Lambs or calves will ingest oocysts when grazing or simply exploring their surroundings. Once ingested, the oocysts will pass through the digestive system to the small intestine. Here, they invade cells in the lining of the gut. These cells’ role is to absorb nutrients from food and water to be used by the animal. Upon invading these cells, the coccidia oocysts begin to develop and multiply. In the process, the gut cells burst and become compromised, releasing more oocysts. Some of these will invade more cells in a repetition of the process and some will pass out with faeces, where they have the potential to infect more animals. In two weeks, a coccidia oocyst can multiply up to a million-fold. The pre-patent period – time from oocysts ingestion to clinical coccidiosis symptoms – is approximately 21 days.

Learn more about Coccidiosis by reading our brochure here.

Watch our SQP/RAMA Training on Coccidiosis and Dycoxan. given by Jonathan Moore, Technical Support Manager with Chanelle Pharma.

Coccidiosis is a disease caused tiny, single-celled parasitic organisms called protozoa. In recent years the condition has become more prevalent with the intensification of cattle and sheep farms in Ireland and the UK.

Coccidia oocycts are numerous in the farm animal’s environment and exposure of livestock to these at some point is inevitable. Oocysts are extremely resilient and can survive in most environments for over 12 months. Under the right conditions they become infective and can cause harm to our animals. Unfortunately, these conditions mirror the warm, moist climate found here in Ireland and the UK. Lambs or calves will ingest oocysts when grazing or simply exploring their surroundings. Once ingested, the oocysts will pass through the digestive system to the small intestine. Here, they invade cells in the lining of the gut. These cells’ role is to absorb nutrients from food and water to be used by the animal. Upon invading these cells, the coccidia oocysts begin to develop and multiply. In the process, the gut cells burst and become compromised, releasing more oocysts. Some of these will invade more cells in a repetition of the process and some will pass out with faeces, where they have the potential to infect more animals. In two weeks, a coccidia oocyst can multiply up to a million-fold. The pre-patent period – time from oocysts ingestion to clinical coccidiosis symptoms – is approximately 21 days.

The breakdown of cells lining the gut leads to a dark, bloody diarrhoea – the most well-known coccidiosis symptom. Other symptoms include straining, dehydration, anaemia, fever, lethargy and in some cases death. However, coccidiosis is a largely subclinical disease. Based on a review of the literature, only 4% of infected calves and lambs will display clinical symptoms (see below).

However, in the same trials, coccidiosis infection reduced growth rates in all animals by between 7% and 33%. The average performance reduction was 19% - based on animals treated in preventative manner with anti-coccidial medicines versus non-treated animals.

.webp)

Given that there is an inverse relationship between age and feed efficiency (young animals are more feed efficient than older animals), symptomless coccidiosis has a significant opportunity cost for farmers. This is particularly true where weight-based age targets are important. For example, in dairy and beef cow herds with defined calving seasons, heifer calving age is a vital target and reduced growth rates in younger animals can negatively affect heifer fertility and longevity in the herd. In sheep flocks, symptomless coccidiosis can increase lamb drafting age and concentrate feed bills where creep feeding is practiced.

Anti-coccidial active ingredients like diclazuril and toltrazuril disrupt the coccidia lifecycle in the animal’s intestine, preventing further development, multiplication and oocyst shedding. They work on coccidia already in the animal, and so treatment is best administered approximately 14 days after the animal has entered an environment deemed as ‘high-risk’. However, on most commercial farms, ‘high risk’ encompasses the majority of an animal’s environment. Alternatively, we can time treatments based on farm history, using the product seven days in advance of when symptoms are expected.

Diclazuril and toltrazuril products should be used in a prophylactic (preventative) manner across full groups of animals. Diclazuril or toltrazuril spot treating of animals with clinical coccidiosis symptoms will prevent further shedding and damage to the gut lining, however if symptoms are being observed the gut has already been compromised – potentially permanently. Animal with coccidiosis-induced, or any form of diarrhoea are in danger of dehydration and should receive fluids and electrolytes. Supplementing clinically affected animals with cobalt/vitamin B12 can also help with recovery.

.webp)

The reason for such precise recommendations around treatment timing is to allow the animal to receive a certain level of exposure to coccidia. This is vital for building natural immunity, which protects older animals from succumbing to clinical symptoms and performance reduction brought about by coccidiosis. However, while a certain level of exposure is desirable in young animals to develop this immunity, high oocyst burdens place strain on, and can overwhelm, the immune system. The subclinical performance reduction caused by coccidiosis is as a result of a diversion of nutrients towards immune responses to the invading parasite. Symptoms occur when this immune response is inadequate, which can be due to an excessively high environmental oocyst burden but can also exacerbated by stressor events weakening the immune system. On a commercial farm, such events might include extreme weather, weaning, dehorning, transport or dog attack.

Provided management around lambing time (including ewe nutrition) is optimal, a certain level of dam-derived (colostrum) immunity to coccidiosis will be transferred to the lamb. From three to four weeks of age this will begin to wane and so we can expect symptoms from six weeks. Multiple lambs and those receiving sub-optimal quality or volumes of colostrum can develop symptoms sooner. Calves do not receive significant protection against coccidiosis via colostrum.

Anti-coccidial compounds like diclazuril or toltrazuril should form part of a multi-modal approach to disease prevention. Optimal hygiene in housing can help to reduce the environmental coccidia oocyst burden and reduce pressure on the animal’s immune system.

.webp)

A number of practical measures can be taken, including:

- Being liberal with bedding and changing regularly – calves should be able to nest in straw pens. Legs should not be visible when calves are lying in straw.

- Avoid soiled, wet bedding – a farmer should be able to kneel on a straw bed and rise with dry trousers.

- Keep water troughs off the ground in sheds to reduce the chance of faecal contamination.

- Locate water troughs outside feeding barriers.

- Chop edible straw and mix it through concentrate creep feed to discourage the consumptino of bedding material.

- Clip cows’ tails in advance of calving.

- Using appropriate disinfectants between seasons e.g. amine-based, ammonium hydrochloride, chlorocresol or p-chloro-m-cresol. Not all disinfectants will work against coccidia. Lime will not kill coccidia oocysts.

- Allow a cleaned-out (fully free of faecal matter) pen to dry before disinfecting and don't bed a wet pen.

However, animals commonly experience high burdens of coccidia oocysts on pasture too, particularly when they begin to graze. In order to minimize the risk at pasture, take the following steps with young animals.

- Set aside clean pasture – ground that hasn’t carried animals on it for 1 year – for young animals where possible.

- If this is impractical, turn young animals into silage ground or reseeded fields.

- Avoid poaching around troughs and creep feeders.

- Avoid fields with direct access to watercourses.

- Target fields with shelter (to minimize stress)

On a typical farm, it is extremely difficult to keep environmental coccidia oocyst burden below a point at which it is detrimental to animal health, year in year out. This is where anti-coccidial compounds like diclazuril or toltrazuril have a role to play.

On farms with high stocking rates and/or high environmental coccidia oocyst burdens (e.g. enclosed systems, farms using same nursery field annually), a second treatment may be required 21 days following the first.

Ideally, the aim should be to treat once and minimize the subsequent environmental burden to an extent that the animal’s natural immunity can develop enough to overcome it.

Although coccidiosis affects a wide variety of animals, the organisms involved are host-specific – coccidia from one species (e.g. sheep) cannot infect another (e.g. cattle). Even species as closely related as sheep and goats cannot infect each other. Three species of Eimeria, the cocci-causing genus, are considered pathogenic in cattle: Eimeria bovis, E. zuernii and to a slightly lesser extent E. albamensis. In sheep, E. crandallis and E. ovinoidalis are the strains for consideration.

Use the solutions below with our FAQ and Best Practice sections to make good decisions on coccidiosis control.

Use medicines responsibly.

The breakdown of cells lining the gut leads to a dark, bloody diarrhoea – the most well-known coccidiosis symptom. Other symptoms include straining, dehydration, anaemia, fever, lethargy and in some cases death. However, coccidiosis is a largely subclinical disease. Based on a review of the literature, only 4% of infected calves and lambs will display clinical symptoms (see below).

However, in the same trials, coccidiosis infection reduced growth rates in all animals by between 7% and 33%. The average performance reduction was 19% - based on animals treated in preventative manner with anti-coccidial medicines versus non-treated animals.

.webp)

Given that there is an inverse relationship between age and feed efficiency (young animals are more feed efficient than older animals), symptomless coccidiosis has a significant opportunity cost for farmers. This is particularly true where weight-based age targets are important. For example, in dairy and beef cow herds with defined calving seasons, heifer calving age is a vital target and reduced growth rates in younger animals can negatively affect heifer fertility and longevity in the herd. In sheep flocks, symptomless coccidiosis can increase lamb drafting age and concentrate feed bills where creep feeding is practiced.

Anti-coccidial active ingredients like diclazuril disrupt the coccidia lifecycle in the animal’s intestine, preventing further development, multiplication and oocyst shedding. They work on coccidia already in the animal, and so treatment is best administered approximately 14 days after the animal has entered an environment deemed as ‘high-risk’. However, on most commercial farms, ‘high risk’ encompasses the majority of an animal’s environment. Alternatively, we can time treatments based on farm history, using the product seven days in advance of when symptoms are expected.

Diclazuril products like should be used in a prophylactic (preventative) manner across full groups of animals. Diclazuril spot treating of animals with clinical coccidiosis symptoms will prevent further shedding and damage to the gut lining, however if symptoms are being observed the gut has already been compromised – potentially permanently. Animal with coccidiosis-induced, or any form of diarrhoea are in danger of dehydration and should receive fluids and electrolytes. Supplementing clinically affected animals with cobalt/vitamin B12 can also help with recovery.

.webp)

The reason for such precise recommendations around treatment timing is to allow the animal to receive a certain level of exposure to coccidia. This is vital for building natural immunity, which protects older animals from succumbing to clinical symptoms and performance reduction brought about by coccidiosis. However, while a certain level of exposure is desirable in young animals to develop this immunity, high oocyst burdens place strain on, and can overwhelm, the immune system. The subclinical performance reduction caused by coccidiosis is as a result of a diversion of nutrients towards immune responses to the invading parasite. Symptoms occur when this immune response is inadequate, which can be due to an excessively high environmental oocyst burden but can also exacerbated by stressor events weakening the immune system. On a commercial farm, such events might include extreme weather, weaning, dehorning, transport or dog attack.

Provided management around lambing time (including ewe nutrition) is optimal, a certain level of dam-derived (colostrum) immunity to coccidiosis will be transferred to the lamb. From three to four weeks of age this will begin to wane and so we can expect symptoms from six weeks. Multiple lambs and those receiving sub-optimal quality or volumes of colostrum can develop symptoms sooner. Calves do not receive significant protection against coccidiosis via colostrum.

Anti-coccidial compounds like diclazuril should form part of a multi-modal approach to disease prevention. Optimal hygiene in housing can help to reduce the environmental coccidia oocyst burden and reduce pressure on the animal’s immune system.

.webp)

A number of practical measures can be taken, including:

- Being liberal with bedding and changing regularly – calves should be able to nest in straw pens. Legs should not be visible when calves are lying in straw.

- Avoid soiled, wet bedding – a farmer should be able to kneel on a straw bed and rise with dry trousers.

- Keep water troughs off the ground in sheds to reduce the chance of faecal contamination.

- Locate water troughs outside feeding barriers.

- Chop edible straw and mix it through concentrate creep feed to discourage the consumptino of bedding material.

- Clip cows’ tails in advance of calving.

- Using appropriate disinfectants between seasons e.g. amine-based, ammonium hydrochloride, chlorocresol or p-chloro-m-cresol. Not all disinfectants will work against coccidia. Lime will not kill coccidia oocysts.

- Allow a cleaned-out (fully free of faecal matter) pen to dry before disinfecting and don't bed a wet pen.

However, animals commonly experience high burdens of coccidia oocysts on pasture too, particularly when they begin to graze. In order to minimize the risk at pasture, take the following steps with young animals.

- Set aside clean pasture – ground that hasn’t carried animals on it for 1 year – for young animals where possible.

- If this is impractical, turn young animals into silage ground or reseeded fields.

- Avoid poaching around troughs and creep feeders.

- Avoid fields with direct access to watercourses.

- Target fields with shelter (to minimize stress)

On a typical farm, it is extremely difficult to keep environmental coccidia oocyst burden below a point at which it is detrimental to animal health, year in year out. This is where anti-coccidial compounds like diclazuril have a role to play.

On farms with high stocking rates and/or high environmental coccidia oocyst burdens (e.g. enclosed systems, farms using same nursery field annually), a second treatment may be required 21 days following the first.

Ideally, the aim should be to treat once and minimize the subsequent environmental burden to an extent that the animal’s natural immunity can develop enough to overcome it.

Although coccidiosis affects a wide variety of animals, the organisms involved are host-specific – coccidia from one species (e.g. sheep) cannot infect another (e.g. cattle). Even species as closely related as sheep and goats cannot infect each other. Three species of Eimeria, the cocci-causing genus, are considered pathogenic in cattle: Eimeria bovis, E. zuernii and to a slightly lesser extent E. albamensis. In sheep, E. crandallis and E. ovinoidalis are the strains for consideration.

Use the solutions below with our FAQ and Best Practice sections to make good decisions on coccidiosis control.

-Postmortem-Farm-Health-First-Powered-by-Channelle-Group.webp)